Of all the changes from DSM-IV to DSM-5, I am most keenly interested in the reframing of substance-related disorders and the related inclusion of gambling disorder as an “addictive disorder.” I spent several years working on a chemical dependency unit in a psychiatric hospital, and my main role was providing psychoeducational groups to adolescent patients who were diagnosed with a substance-related disorder. I also accompanied the patients to Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meetings several times per week. One of the more challenging aspects of the job was that these inquisitive young patients often questioned me and other staff members about the many contradictions they perceived between AA’s philosophy/approach, the information packets about chemical dependency provided by the hospital, and their own life experiences related to substance use and abuse. For instance, they might say something like the following:

Of all the changes from DSM-IV to DSM-5, I am most keenly interested in the reframing of substance-related disorders and the related inclusion of gambling disorder as an “addictive disorder.” I spent several years working on a chemical dependency unit in a psychiatric hospital, and my main role was providing psychoeducational groups to adolescent patients who were diagnosed with a substance-related disorder. I also accompanied the patients to Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meetings several times per week. One of the more challenging aspects of the job was that these inquisitive young patients often questioned me and other staff members about the many contradictions they perceived between AA’s philosophy/approach, the information packets about chemical dependency provided by the hospital, and their own life experiences related to substance use and abuse. For instance, they might say something like the following:

“I personally know several people who used drugs heavily for years and then quit or cut down on their own, without any treatment centers or twelve step groups. So, why is everybody here telling me I can’t stop getting high on my own, that I’m powerless over the ‘disease of addiction’?”

I found it difficult to integrate the various perspectives about substance use problems in a way that made clear sense to these young patients (and to myself as well!). DSM-IV focused on the distinction between substance abuse and substance dependence; the twelve steps focused on admitting one’s powerlessness over the spiritual disease of addiction; the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) described addiction as a chronic, relapsing brain disease; and our hospital treated substance-related disorders from a psychosocial perspective, focusing on group therapy, family therapy, and community support for our patients.

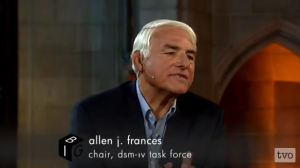

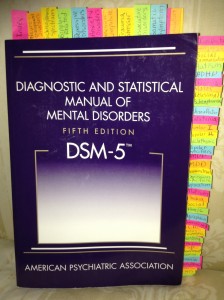

In the years leading up to the publication of DSM-5, I read with interest many media reports about the proposed changes to the substance-related disorders diagnoses. For instance, DSM-IV Task Force chair Allen Frances (2010) lamented that DSM-5 changes would lead to increased mislabeling of people with mild substance abuse problems as “addicts.” Ian Urbina (2012) published a widely read article in the New York Times which claimed that the DSM-5 would reduce the number of symptoms required for a diagnosis of drug/alcohol addiction, which could lead to many more people being inappropriately diagnosed as drug addicts. I was highly sympathetic to these critiques of the DSM-5 changes, that is until I read the DSM-5 chapter on Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders for myself. I discovered that many of the widely publicized critiques regarding this particular change in the DSM-5 were simply inaccurate, at least as they relate to the final published version of the manual. For example, while it’s true that substance use disorder in DSM-5 more or less combines the DSM-IV categories of substance abuse and substance dependence into a single disorder (i.e., substance use disorder), the new manual does not apply the word “addiction” to this class of disorders. The DSM-5 (2013) clearly states that the word addiction, while commonly used by both clinicians and laypersons around the world,

“is omitted from the official DSM-5 substance use disorder diagnostic terminology because of its uncertain definition and its potentially negative connotation” (p. 485).

Also, contrary to the often repeated charge that DSM-5’s general criteria for substance use disorders have been weakened by the combining of the previous categories of abuse and dependence, a strong case can be made that the new criteria have been strengthened:

“Whereas a diagnosis of substance abuse previously required only one symptom, mild substance use disorder in DSM-5 requires two to three symptoms from a list of 11” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, para. 2).

Furthermore, the American Psychiatric Association (2013) makes the case that the previous DSM-IV category of “dependence” was problematic, as people often seemed to associate the concept of dependence with the concept of addiction, causing just the type of confusion I noted above when describing the young patients I worked with at the hospital.

At this early point in my knowledge of the new DSM-5 criteria, I am inclined to see the revised substance use disorder diagnoses — characterized by overarching criteria across substance classes and a severity continuum ranging from mild to severe — as a potentially useful advance in the conceptualization of substance-related disorders. I’m not sure, however, how I feel about the inclusion of gambling disorder in the new category of “addictive disorders.” While I understand the rationale behind this inclusion (i.e., the available research associating disordered gambling behavior with reward systems in the brain that are also linked to disordered substance use), I’m concerned that this linking of substance-related and nonsubstance-related disorders requires a far more extensive re-visioning of the concept of “addictive disorder” than is provided in DSM-5. Assuming that future research establishes and confirms the requisite connections between other “behavioral addictions” (e.g., those related to excessive internet use, sex, shopping, exercise, etc.) and specific reward systems in the brain, another major revision of this DSM chapter will likely be necessary, and that hard-to-define term “addiction” might become even more difficult to understand and talk about!

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Substance-related and addictive disorders (fact sheet). Retrieved October 30, 2013 from http://www.dsm5.org/Documents/Substance%20Use%20Disorder%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf

Frances, A. (2010, March 30). DSM5 “Addiction” Swallows Substance Abuse.

Psychiatric Times. Retrieved October 30, 2013 from

http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/dsm5-addiction-swallows-substance-abuse

Urbina, I. (2012, May 12). Addiction diagnoses may rise under guideline changes. New

York Times. Retrieved October 30, 2013 from

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/12/us/dsm-revisions-may-sharply-increase-addiction-diagnoses.html

![India, 42, suffers from manic depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. She has spent almost all of her adult life in jails and prisons. [John Gress for The New York Times]](http://www.integralhealthresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/09kristof2-articleLarge-300x200.jpg)