I was scrolling through my twitter feed this morning, enjoying my coffee, when I came across the following headline from NPR Health News: “Can’t Focus? It Might Be Undiagnosed Adult ADHD“. My heart sunk. It seems even the smart folks at NPR are not above peddling the dodgy “mental illness as medical condition” narrative. This shouldn’t surprise me. Just the other day I was tuned in to NPR’s Here and Now, a show I totally dig, and I cringed hard as host Robin Young trotted out the whole “addiction is a disease, just like diabetes and cancer” song and dance. I suppose I find it particularly depressing when otherwise smart, sensitive people demonstrate such a profound and consequential failure of critical thinking. And it’s such a touchy subject to discuss. When I say something like “addiction is most definitely not a disease and is nothing like cancer,” people might think I’m saying that addiction itself is not real, or that the suffering addicts experience is not real. As a mental health professional, it is rather inconvenient that my perspective of mental health is at odds with the most prominent points of view. It is simply a fact that vast swaths of people, both in the general public and across mental health professions, buy into the medical model of mental illness, at least to a significant extent. It’s impossible to escape the language of this way of thinking, the talk of “symptoms,” “diagnoses,” and “treatments,” and all the distorted thinking and misplaced actions that follow.

How can I point out, convincingly and with compassion, that it was wrong and potentially harmful for the hero in the NPR story, psychiatrist Dr. David Goodman , to frame his patient’s lack of attentional focus as a medical condition in need of medical treatment? After all, one of the patients (Kathleen) reported that she was completely and positively transformed by Dr. Goodman’s medical treatment, that she can now finally focus her attention, finish projects she’s started, and stop beating herself up for being a stupid or lazy person. It’s a difficult discussion to have, no doubt. But the truth matters. And the truth is that a lack of attentional focus is not caused by a stimulant deficiency, any more than drowsiness is caused by a stimulant deficiency. Yes, stimulants increase focus and alertness in most people. No, a lack of focus and alertness is not a disease or medical condition. Yes, Kathleen, your lack of attentional control might lead to problems, difficulties, and suffering. These problems are real. Your suffering is real. And yes, stimulants may help. But no, you do not “have” a medical condition, a glitch somewhere in your brain, that is being targeted, treated, or cured by the miracles of modern medicine. The truth is, no one, not even Dr. Goodman, knows why you have trouble focusing your attention. Maybe it is partly how you’re “wired.” Maybe your innate attentional tendencies aren’t a great fit in a society that values a laser-like focus of attention over other ways of taking in the world. Maybe your relationship with electronic devices can be tweaked for the better, and that might make a difference. Maybe your diet factors in somehow. Maybe a lot of it has to do with the fact that you are bored as hell with your job. Who knows for sure? Not Dr. Goodman, no matter how impressive he looks in his white jacket with a stethoscope dangling around his neck.

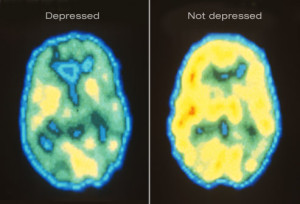

Yes, it may be comforting to externalize your problem as a “treatable disorder.” But you don’t have to choose between “I have the disease of ADHD. It has nothing to do with how I live my life.” and “It’s all my fault. I’m stupid and lazy.” The truth is that psychological problems are complicated. The truth is that ALL behaviors and experiences are rooted in the brain and body, and yet our neurophysiological processes are also constantly being influenced, fashioned, and shaped by what we do in the world, by the actions we take, by the quality of our interpersonal relations and other psychosocial engagements. So go ahead and take the Ritalin, if it helps. But consider the potential side-effects and health impacts first. And don’t buy into to false notion that Ritalin is curing some illness that you have. Buying into that false notion shuts down consideration of all the psychosocial factors that are well worth considering.

The same goes for the vast majority of psychological problems faced by the vast majority of human beings. Are there neurodevelopmental and genetic anomalies that affect some people? Of course! Can the tools of modern medicine be brought to bear on these and other problems? Of course! But if the medical model of understanding mental health problems was effective in addressing the more common concerns of the general population (as it has been with say, vaccinations for various infectious diseases), then we should see a reduction in the severity and rates of mental illnesses as our medical treatments are being increasingly applied. But we don’t see that, and that’s because the vast majority of psychological problems experienced by the vast majority of human beings are not best understood using the conceptual tools of the medical model.

I know a kid, about ten years old, who takes the antipsychotic medication Risperdal to help control his behavioral outbursts. The meds are helping, no doubt about it. Fewer explosive outbursts. Fewer trips to the hospital. Better grades in school. This kid’s problems are real. His suffering is real. His parents’ suffering is real. But this kid doesn’t have a “disease” that is being “treated” by the Risperdal. He’s not suffering from a Risperdal deficiency or from brain damage in some hypothetical neural circuits that Risperdal might be affecting. Perhaps smoking some marijuana every day would help control his outbursts as well, but that would say nothing about the “cause” of his problems. The truth is, no one knows why he is the way he is. It’s complicated. But thinking of his problem as a “brain disease,” however comforting that might be to him and/or his parents, is bad thinking, wrong thinking, and potentially dangerous thinking. That thinking pushes his parents to accept the often severe side effects of Risperdal, the unknown effects on the child’s developing brain, and to close the door on exploring the many other interventions (e.g., physical exercise, dietary changes, parental-style adjustments, creative outlets, behavioral modification strategies) that may also help to control the child’s outbursts. And psychosocial interventions have the distinct advantage of being side-effect-free, while also building skills and positive behaviors that can shape both subjective experiences and neurophysiological structure in enduring ways.

So, going back to the NPR story that started me on this rant, I’m happy that Kathleen is able to focus her attention in a way that’s more to her liking. But I’m not happy to see NPR falling into the same traps of poor thinking that have been keeping the broken mental health model in place for decades. Decade after decade we apply the same medical model to the problems of mental illness and addiction, and decade after decade we scratch our heads wondering why everything keeps getting worse and worse.

What are some alternatives, you might ask? There are plenty of them. Check out, well… anything on this website, for starters!