It’s a new year, and I find myself living in a “post-fact” world of “fake news” with catastrophic failures of critical thinking everywhere on display. Happy New Year everybody! What holds true–if anything holds true these days–in the realm of politics is not fundamentally different from what holds true in other areas of discourse, like say, behavioral health. And that true thing is this: our current capacity for critical thinking cannot seem to adequately process, evaluate, and analyze the constant flow of information that is being channeled through structures designed to further agendas rather than deepen knowledge and improve understanding. That was a mouthful, I know. I just can’t help wondering though, Has all this blogging been just pissing in the wind? Have I myself been duped, or been duping myself, into a false sense of certainty and self-righteousness? Maybe. But at least I’m trying. At least I care enough to ask questions.

The first Friday of every month I attend a continuing education training for mental health professionals. The training takes place in a local psychiatric hospital, and is conducted by various local leaders in the mental health profession. This last training was on the topic of addiction treatment, and I was expecting to get a heavy dose of twelve-step and brain disease dogmatism, and that’s just what happened. What took me by surprise was how starkly unscientific the presentation was–not a single reference to a single piece of research, and how uncritical the audience was as they nodded their heads to statements like “This disease wants you dead!” I felt like I was in a church listening to a sermon. I left the training deflated and discouraged. How can there be any hope of a sane, scientifically grounded approach to drug abuse (or any mental health problem for that matter) when the thought leaders, experts, and armies of professionals are all in lock-step headed in the wrong direction? Fortunately, there are dissident voices breaking through via the internet ether waves. But again, perhaps I have constructed my own cozy echo-chamber in this regard. You be the judge.

Johann Hari, he of “Chasing the Scream” and TED notoriety, wrote an interesting op-ed in the LA Times the other day called “What’s really causing the prescription drug crisis?” The piece pokes holes in the most well-subscribed narrative regarding the current opiate crisis in America, namely that Big Pharma has hooked everyone on irresistible drugs, and that what we need to do now is restrict access to these powerful life-ruining substances. The holes in this theory might not seem obvious. Even John Oliver, whose entertaining critiques usually strike the right tone, seems to have blown past them.

First of all, Hari points out that less than one percent of opiate prescriptions lead to addiction, and that super strong opiates (like diamorphine) are routinely administered in hospital settings in other countries without causing people to become addicted. So, then, the drugs themselves can’t be root of the problem, right? If it were the drugs themselves, then opiate addiction should be spread evenly across the country to match prescription rates. But it isn’t. Opiate addiction is concentrated in areas where times are the toughest, like in the Rust Belt. It’s the tough times–and their impact on people who may lack the resources (internal and external) to cope with them–that are more likely to be the root of the problem, rather than any specific numbing agent. Furthermore, how can stringent opiate restriction be the best response to the problem, when the vast majority of people who use the drugs to manage pain don’t show problematic use, and when cutting addicted folks off from their prescriptions so clearly leads them to black market heroin use? This “War on Drugs” mentality might be well-intentioned, but it’s just making things worse. In order to come up with a more effective solution, we need to fully understand the problem, which means taking into account all of the facts, which would lead us toward addressing root causes (like poverty, social isolation, poor coping skills) instead of restricting the latest, most available, most potent means of killing the associated pain.

Of course, addiction is just one category of so-called “mental illness,” and a broader argument can (and has) been made against viewing problems of thinking, feeling, and behaving, in general, as biologically driven processes best suited for physiologically focused interventions. I have been pissing in that wind for years as well, but I have not come across a more thorough critique of the predominant psychiatric paradigm than in this recent article by Phil Hickey called The Biological Evidence for “Mental Illness.” Hickey makes many of the points that I have made–ad nauseam–in previous posts (e.g., HERE), but he makes them far more meticulously and convincingly. He also grounds his arguments in research and years of clinical experience. Here are a few of Hickey’s ideas from this article that are well worth chewing on:

Depression, either mild or severe, transient or lasting, is not a pathological condition. It is the natural, appropriate, and adaptive response when a feeling-capable organism confronts an adverse event or circumstance. And the only sensible and effective way to ameliorate depression is to deal appropriately and constructively with the depressing situation. Misguided tampering with the person’s feeling apparatus is analogous to deliberately damaging a person’s hearing because he is upset by the noise pollution in his neighborhood, or damaging his eyesight because of complaints about litter in the street.

What psychiatry calls mental illnesses are actually nothing more than loose collections of vaguely-defined problems of thinking, feeling, and/or behaving. In most cases the “diagnosis” is polythetic (five out of nine, four out of six, etc.), so the labels aren’t coherent entities of any sort, let alone illnesses. But the problems set out in the so-called symptom lists are real problems. That’s not the issue. I refer to these labels as inventions, because of psychiatry’s assertion that the loose clusters of problems are real diseases. In reality, they are not genuine diseases; they are inventions. They are not discovered in nature, but rather are voted into existence by APA committees.

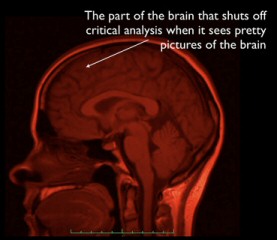

Both Hari and Hickey hit the nail on the head by pointing out what should be obvious, namely that addiction and other psychological problems are most often matters of adaptation, of learning, which are process that all healthy, normal brains participate in as they interact with their respective environments. How else could it be that the vast majority of people with such problems get better through such means as talking things out, rearranging their priorities, determination to change habits, and improving relationships? While it’s true–again, obviously–that every subjective human experience is grounded in some activity happening in the brain from moment to moment, it is sheer nonsense to assume that common problems faced by vast numbers of human beings are matters of hardware malfunction. This might be true for the very few. But it is only through misaligned incentives and misapplied critical thinking that the brain disease paradigm has become mental health dogma.

*Mic drop*