It seems reasonable to assume that if you want to know about a given topic, a good place to start is by checking out what the leading experts in the field have to say about it. For instance, if you google the word “addiction,” you pretty quickly are led to HBO’s Addiction Project site, which contains loads of information backed by such heavy-weights as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). So what is addiction, according to the leading experts?

It seems reasonable to assume that if you want to know about a given topic, a good place to start is by checking out what the leading experts in the field have to say about it. For instance, if you google the word “addiction,” you pretty quickly are led to HBO’s Addiction Project site, which contains loads of information backed by such heavy-weights as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). So what is addiction, according to the leading experts?

Addiction is a chronic relapsing brain disease. Brain imaging shows that addiction severely alters brain areas critical to decision-making, learning and memory, and behavior control, which may help to explain the compulsive and destructive behaviors of addiction.

Ah yes, the brain. The three pound hunk of tofu that is the ultimate source of all problems and all answers. (Deep, prolonged sigh.) Of course it’s true that any human behavior or experience can be understood in terms of neurobiology and brain states, and it’s also pretty clear that this understanding is valuable and worth pursuing. But it simply doesn’t follow—in theory or in practice—that therefore dysfunctional behaviors and experiences are neurobiological diseases. In our everyday lives, we take for granted that human life is complicated and plays out on many levels. And long before “neuroplasticity” became a buzz word, we already knew that what we do, how we use our attention, and how we relate to one another affects the quality of our lives (and the structure and function of our bodies/brains).

I worked on a chemical dependency unit in a psychiatric hospital for several years, and I’m fairly certain that most of the professional staff would accept information provided by NIDA (and most everything on the HBO site) uncritically, as I’m sure it fits seamlessly with what they learned in graduate school. But young people tend to question everything, and the patients I worked with were anywhere from 12 to 18 years old. Part of my job was to lead educational discussion groups with these kids several times a week. I also accompanied them to Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings several times a week. These kids constantly questioned staff members about all the contradictions they perceived between AA’s philosophy, the treatment center’s information packets, and their own life experiences. For the most part, the contradictions the kids brought up were crushed by the weight of authority, not cleared up by reasoned argument and explanation. I was quite often in the awkward position of covering for and/or attempting to recast the many misconceptions served up daily and repeatedly to patients, some of whom were desperate for accurate information. The kids (who were almost all cigarette smokers) would inevitably point out things like: “Nicotine is super addictive, right? Well, I personally know several people who quit smoking on their own, without any treatment centers or twelve step groups. So, why is everybody here telling me I can’t stop getting high on my own, that I’m powerless over the ‘disease of addiction’?”

As Stanton Peele (one of the few clear-thinking “leading experts” on addiction I’ve come across) has been pointing out for decades, addiction is and has always been politically and socially defined as much as it has been scientifically defined. Peele covers this ground thoroughly in his recent article The Fluid Concept of Smoking Addiction:

The neurobiological model of addiction is static. It is built on the difficulty – often stated as the near impossibility – of quitting or moderation. The model does not attempt to explain how (or, more accurately, why) people cease addictions – even though such cessation is more typical than not with every type drug. The neurobiological model really has nothing to say about why smokers quit (as a majority do), for example due to the pleading of a spouse or a child. In the terms of the model, cessation is unexpected, unexplained, unpredictable, and simply falls beyond its purview or boundaries.

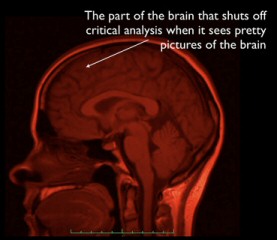

I used an Integral Health framework to help my patients make sense of their substance abuse problems. In practice, our entire staff operated under the integral premise, i.e. that we must address every conceivable dimension of the patient’s life if we hope to make the most effective impact. Some patients, especially those who were heavy opiate users, were given (non-narcotic) drugs to deal with their withdrawal symptoms. Other than that, there was little about the treatment program that had anything to do with directly impacting brain chemistry. We helped patients become more aware of their thought patterns. We taught them healthy coping strategies to deal with the challenging situations and emotions that would inevitably continue to crop up in their lives. We brought their families in for counseling sessions. We contacted teachers, probation officers, judges—anyone who would be working with these kids once they were discharged back into their respective communities—and developed detailed aftercare plans. We covered all the bases, because we knew that substance abuse problems both develop and are potentially resolved in a multidimensional, bio-psycho-sociocultural context. Surely, most thoughtful people (including the folks at NIDA) know this to be true, and yet the “leading experts” continue to present their oversimplified, disingenuous “brain disease” model to the public (complete with brain scan images that often signify very little, and the obligatory lip-service footnote containing the term “biopsychosocial”). I confess, I’m not entirely sure why this is the case. I suspect it has something to do with how government and academic institutions secure their funds. The more influence the pharmaceutical industry has on research and policy processes, the more traction the brain disease model seems to get. And, of course, the public eats up (literally, in the case of pills) easy answers and quick-fix remedies that require as little life-style change and psychological work as possible.

So, although it may seem reasonable to rely on the opinions of leading experts in a given field, this doesn’t always hold true when it comes to the field of mental health. Integral and integrative understandings of addiction and other problems do exist, but they haven’t yet had the appeal and/or financial backing required to capture the imagination of either the leading experts or the general public.

On the bright side, I’m sure all this will change once I click the “Publish” button and everyone on the internet reads this blog post!